Part 2 : Menhaden and modern industry

Part 2: Western historical references to menhaden along the eastern seaboard date back to the early 17th century, when explorers like John Smith documented the region’s rich fisheries. The species appear throughout early colonial history—famously when the Wampanoag native Tisquantum (“Squanto”) taught the Pilgrims to use them to fertilize their fields.

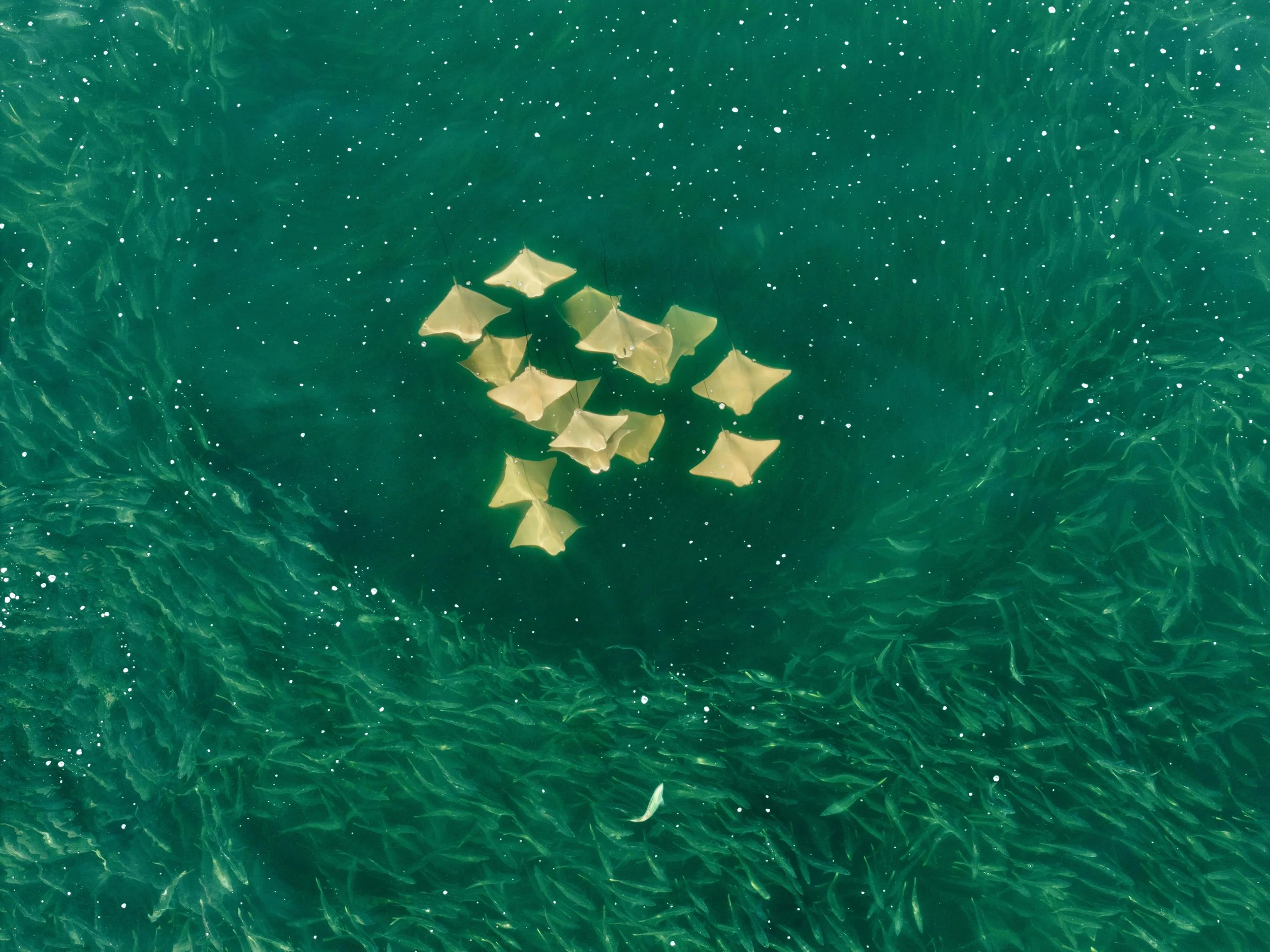

Reports from the early 1800s describe menhaden as so abundant they were often driven ashore by predators like sharks and bluefish—around the same time, commercial reduction for oil began in Connecticut and on Long Island. The industry grew slowly at first, but with the spread of the Industrial innovations like the hydraulic press, factories appeared from Maine to Virginia.

From 1873 to 1877, over 60 factories processed ~500 million menhaden each year. With humpback whales hunted to near extinction and few alternatives, menhaden oil became a cheap, abundant substitute. By 1950, the yearly catch had grown to 1.5 billion fish. First harvested for oil and fertilizer, they’re mainly used for fishmeal and oil today.

Because menhaden were integral to the nation’s growth, the fishery went largely unchecked through World War II. By the late 20th century, the population had nearly collapsed, with mature adults estimated at 13% of their levels four decades earlier. Overfishing, pollution, climate change, and habitat degradation contributed to steep declines

Factories consolidated or closed—partly due to odor regulations, but also poor year classes and declining catches. By 2006, only one reduction plant remained: Omega Protein, based in Reedville, Virginia, still operating today under Canadian ownership.

In 2012, the ASMFC reported one of the lowest menhaden populations on record, leading to the first coast wide catch limit (TAC). It was a step toward recovery, though newer research suggests populations are lower than current limits reflect. The restrictions initially helped rebuild stocks—by 2019, menhaden had rebounded to numbers unseen in decades—but recent data shows populations shifting again, and management still fails to fully account for their ecological role.